|

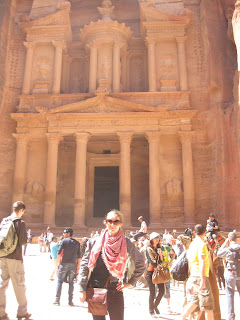

| Me in front of Petra's Treasury. |

Pursue some path, however narrow and crooked, in which you can walk with love and reverence.

-Henry David Thoreau

I always finish an odyssey down to the Post Office with a

good story. While most of my mail can be sent to the Fulbright House directly,

where I have a personal mailbox, the government refuses to let a package

through without a customs check. All international parcels get funneled into

the main post office in the busy center of downtown Amman, where they sit

collecting fines and fees until its recipient goes through the humorously long,

bureaucratic process of retrieving it.

When I receive a formal e-mail from the Fulbright

administration that I have, in fact, received a package, I fix my determined

gaze on my planner to find the best time I should attempt to retrieve the

parcel. Regular office hours technically exist, but I’ve had a handful of

experiences where I’d arrive only to find the office closed for a holiday, or

for maintenance, or for no reason at all. To avoid these failed attempts as

much as possible, I go early in the day, leaving my house at seven in the

morning to take the twenty minute walk of winding stairs down the steep slopes

of my neighborhood, Jebel Amman, to downtown.

Everyone knows I’m no morning person, but even if I need to

mentally prepare myself for an early rise, I quietly enjoy walking in the first

morning light and experiencing the peaceful side of Amman waking up from a cool

night. The crisp air warms with every inch higher the sun rises. I admire the

long, looming shadows cast by the quiet homes. They provide a stark contrast

from the brilliant orange glow of the morning sun against the white sandstone

facades. I see men silently take their morning cup of coffee in the solitude of

their balcony and women opening their windows to welcome a new day. It’s

beautiful.

Conveniently, perhaps the most convenient part of such a

trip, the stairs leading downtown arrive directly in front of the post office, whose

humble entrance gives you no indication of the sprawling mess of bureaucracy

within. I cross the street, empty of speeding cars and meandering people at

this hour. Entering the post office and walking up the stairs, a cacophony of

noise greets me, increasing in volume with every step. A series of strange

typewriter-like clicks, grumbling employees’ voices, quick footsteps, and

telephone rings fills my ears as I enter the room and approach the first clerk.

“Number, habibti?” the bored, greying man asks me for the

package number.

“One hundred and sixty-three,” I say in Arabic.

“One, six, three?” he checks with me in English. I nod and

smile. He takes out a half-meter-long stack of receipts and starts leafing

through them. Apparently, they have no particular order, because he’s looking

at every paper. After a minute of this, I timidly offer, “And my name is Sarah

McKnight.”

“Sarah what?”

“McKnight.”

“Might? What?”

“McKnight, like son of a knight,” I explain in Arabic.

He only raises a confused eyebrow, laughs, and continues his

perusal. About three minutes later, he finds my paper. “Oh, McKnight,” he

realizes with a grin, reading my information. “Interesting name. You’re not

Arab?” he jokes, “Go to the next room, habibti.”

I take the receipt with a polite nod and follow his gesture

pointing in the direction of a small room in the far corner, where two men sit

smoking and writing things in ledgers. The first take my phone number and shouts

at a man in the next room over. The second man is the customs officer. I have

to open the package in front of him and watch as he inspects everything to see

if there’s anything taxable.

My first experience with this gentlemen was quite shocking.

My mother, not knowing that anyone but me would be rifling through the box, had

last-minute thrown in a pair of forgotten underwear that I’d left behind during

my last visit to Kentucky. So, upon opening the box and handing it over to the

inspector, I realized what was sitting on top of everything else and grimaced

in anticipation for the awkward situation I was about to have. Jordan, a

country with a conservative culture, does not leave much room for men and women

to interact in the social sphere, and therefore far less room for interaction

with unmentionables.

The officer, sipping a dainty cup of Turkish coffee and

smoking a cigarette, used his cigarette-laden hand to pick up the underwear. I

watched the muscles in his face tighten and heard him stifle choking sounds. He

immediately dropped the article and I said, “From my Mom,” as if that would

make the situation better. He ignored me and wrote on my receipt. I suppose the

customs inspection immediately stopped there. All the better for me, since it

garuanteed me no customs fee.

This time, however, my interaction with the officer was

pleseantly devoid of any awkward moments. My mother cleverly hid my birthday

present between stacks of chocolate bars, and the stolid inspector found

nothing to tax.

After he nods at me to go through the rest of the process, I

take my receipt and go to one room for a stamp and signature, another room for

a stamp and signature, and yet another room for another stamp and signature.

The signers are other officers in uniform who usually have other officers over

for coffee and discussion.

After this formal series of officiants, I finally take the

receipt to the cashier. Usually, I only pay a dinar for the postal services. This time, however, the

cashier tells me, “Four dinars and thirty kirsh.”

“What? Why?” I ask.

“You’re three weeks late on getting your package. You get

fines,” the cashier explains.

“But it was sent three weeks ago,” I say, “That’s when it

was sent.” The cashier shakes his head and shrugs. I realize I have to either

spend an hour to negotiate out of three dinars, or I can pay and leave. I sigh

and pay the fine, kicking myself for supporting a faulty system. But my

frustration quickly dissipates as I pick up the package and gaze in awe at all

the goodies to behold.

I jump giddily down the entrance steps and back out into the

brilliant sunshine. Amman has woken up and is now humming with energy. Cars

have filled the streets, vendors have opened their shops, and kids are bouncing

on their way to school.

With a deep breath of fresh air, I begin to make my way up

the stacks upon stacks of steps, back up to Jebel Amman. The path that felt

like a convenient jaunt now seems like a sweaty, impossible death march. Yet I

can’t justify getting a taxi when my home is so close and I could always use

the exercise. I find one of my favorite passageways to scale the last stretch

of height up to the top of the hill. Its shady staircase with crumbling steps

gives me a cool place to take my time.

Finally, I take the last step and heave myself onto the

quiet side street. I take a few breaths and then continue my walk, but then I

studdenly hear a psssssst and turn

around in shock. Usually, predatory young men make this sound to taunt young

women, but this time, I see that it’s a smiling, middle-aged woman coming

towards me. I take a deep breath of relief and she says, “What a

beautiful thing to come out of those stairs!”

My bashfulness and lack on fluency only allow to manage a, “Thank

you.”

“You must be tired after that walk,” she observes, “Good, then welcome, come

to my house and we’ll drink tea.”

I’ve never met this kind woman before, but I instinctually

trust her already. “Oh, thank you so much,”

I repeat, then say, “Unfortunately, I’m so busy.”

“Naturally,” she

smiles and nods.

“But next time,” I assure her.

“God willing,” she says.

“God willing,” I nod. We share a warm-hearted smile with

her. “Go with peace,” I give her the formal, Arabic farewell.

“With peace,” she turns away, still smiling, and starts her

way down the same stairs. I smile as I realize that I’ve never seen anyone else

use that staircase.

Moments like these make me love Amman.