|

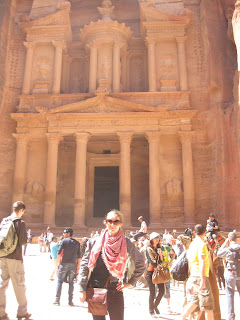

| Me in front of Petra's Treasury. |

Saturday, May 5, 2012

Walking to the Post Office

Friday, April 13, 2012

Love from Egypt

"Denial isn't just a river in Egypt."

- Mark Twain

Here's a photo of me at the Cave Churches, posing with a bunch of adorable kids.

What a crazy couple of weeks! Right after I finished my final stretch of Arabic courses, I took my Mom and sister Norah on a whirlwind tour of Jordan. We floated in the Dead Sea, wound our way around the hazardous mountain roads, strolled through the gorges of Petra, sang with Bedouins in Wadi Rum, and finally relaxed on the shores of the Red Sea near Aqaba.

Of course, a week of tourism wasn’t enough. As soon as Mom and Norah flew off for home, I was plotting my next adventure. My college roommate Asmaah was visiting her family in Egypt and had invited me to tour the country with them. The offer was tempting, a rare opportunity to see a particularly challenging country with people who knew and took pride in its culture.

So, four days later, I had a luxuriously laid-back day of flying from Amman to Luxor, where I would meet up with Asmaah and her parents. I stepped out of Luxor’s small airport and into the sunny afternoon, complete with warm breezes and Asmaah squinting through the sunset’s intensely orange light to spot me. After heartfelt, hug-filled greetings, we took a trundling van ride over the bumpy streets of Luxor to the grand Nefertiti Hotel. I watched about 20 minutes of reality TV before I crashed, and I didn’t regain consciousness again until the groggy hotel clerk rang me at 4 in the morning to inform me that my hot air balloon was waiting.

I rushed to get ready and ran down the stairs to hop into another van with Asmaah and her Mom, from whence we took a sunrise felucca ride across the Nile to our balloon. We watched in amazement as we approached the take-off field, where a handful of parachute-sized balloons billowed majestically in the early morning breeze as a crew of men ran around and commandeered the machines that blew flames of burning gas into their mouths.

Our guide shouted to get our attention. “Remember,” he yelled, “When we land, you need to crouch low in the basket. Usually, we have a nice, soft, what we call an ‘Egyptian landing.’ But sometimes, we have an ‘American landing,’ where the basket bounces a few times across the ground before it stops. And then sometimes we have an ‘English landing,” where the basket tips over to its side and everyone falls out. So, just in case the wind blows hard and gives us an English landing, stay low in the basket, yeah?”

We all laughed and followed him to the basket that was waiting for us. Once we had all filed in, the guide had us up in the air and soaring over Luxor in a swift, effortless minute. In that minute, I could think of nothing but the view, the powerful expanse of desert divided by the winding Nile River that cradled lush, green fields and ran calmly into the infinity of the horizon. We hung over the basket’s side as we drifted over people’s homes. Families looked up and waved to us. Despite their kind gestures, I couldn’t help but feel guilty as I waved back, that I was getting an unfair view into their lives. The sounds of farm animals echoed up to us as we watched the creatures roam along roofs or courtyards.

“Alright, everyone,” our guide called out, “Get into landing positions!” Before I knew it, we were quickly approaching the ground, gliding over a farmer’s field. “Looks like we might have an English landing.” Some of us laughed nervously as we hastily crouched down and braced ourselves for landing. With the first bam, I knew we would have an American landing, but after some bouncing and skidding we landed right by a roadside. The farmers, plowing their field, only glanced at us once or twice. They must be used to balloons landing in their fields?

After our flight, we toured Luxor and Aswan in record fashion, touring a Pharaoh’s tomb or temple after another. I ran around the temple, gazing at the rows upon rows of hieroglyphs like a 6-year-old in a candy shop, trying to memorize sounds for as many symbols as I could.

When we had to pay an entrance fee, Asmaah’s mother had a fun time trying to get me in for the Egyptian price. Tourist spots usually list three different prices: the unnecessarily high foreigner’s fee, the somewhat reasonable international student price, and the incredibly low Egyptian price. “She’s Egyptian?” the ticketer would ask, gawking at my incriminating, blonde hair. “Of course!” Asmaah’s mother would reply. Naturally, some wouldn’t buy it. Upon further inspection, they would demand that I at least pay the international student fee, but not after Asmaah’s mother had given them an earful about the unfair treatment of foreign-born Arabs (the story we adopted was that I was half Arab). It was great.

Though we were busy, we always found some time to relax, whether on a quiet boat ride on the Nile or a pleasant stroll through banana orchards. I found time to savor the deliciously fresh fruits that gave me an explosion of flavor with each bite.

After our fun but tiring speed tour through the South, we had a restful day-long train ride up to Cairo, where the city’s overwhelming craziness smacked me in the face the moment the train doors opened. Cars speeding by, people yelling at each other, music blaring out of store fronts, children racing through the crowds, all mixing into a cacophony of noise I’ve never experienced before. Sitting numb in the back of an ancient taxi that zigzagged its way through traffic, I found a small part of myself missing the serene atmosphere in Amman.

If Cairo’s insanity lost me, the city’s food brought me right back. I loved it all: the savory, grilled lamb cutlets; the freshly fried falafel, the just-caught and seared fish; the ripe fruits and vegetables.

And, of course, we toured the Pyramids. In a horse-drawn carriage, we gazed at them in respectful appreciation. Occasionally, our guide would stop us for photos, telling us to pose in different angles: “Okay, now crouch down… okay, now pretend you’re putting your finger on the top of the Pyramid… okay, not pretend you’re putting sunglasses on the Sphinx…”

In my last day in Cairo, my mother’s friend Mumtaz toured me around a Coptic Christian area known as Garbage City, thus named because the residents have made an occupation out of sorting through truckloads of the city’s trash for recyclables. It was the first area of Cairo where I saw that most of the women did not cover their head. Parts of the neighborhood smelled of decaying organic waste. I covered my nose, and Mumtaz explained, “Yes, before the Swine Flu scare, pigs used to roam the streets and eat all the extra waste. But the Swine Flu hit and the government killed all the pigs, so now the people have difficulty with getting rid of all the organic materials.”

As we continued walking around, I saw that the neighborhood’s residents lived a hard life. Naturally, sorting through garbage makes a small income. “They live a hard life,” Mumtaz continued, “But they are hard-working, resourceful, and tough.” Every person I made eye contact with smiled, and a stream of children continued to run up to me, shake my hand, and practice their English.

Eventually, we walked through a gate that separated the Cave Churches from Garbage City, and the walls of buildings turned into gardens along a cliffside. True to its name, the Cave Churches is an area that houses a series of Coptic churches in the caves that line the cliff. According to Coptic tradition, a place becomes a church as long as an altar is within the space. Mumtaz showed me every one, each complete with a bedazzlingly ornate altar. It was Sunday, so in one church, over three hundred babies were being baptized at once.

We stepped into another just as the most massive mass I’ve ever seen was proceeding into sharing the Holy Sacrament of the Host. I was trying to imagine how many thousands of Copts were in this one church, lining up for communion. You can only receive communion if you’ve been baptized in the Coptic Church, so we eventually left. At the entrance of this cave, a tattoo stall advertised cheap tattoo crosses. Many of the mothers who had just baptized their babies were waiting in line to get their child’s wrist tattooed. As I saw a child shrieking in pain, I squirmed at the idea of causing a helpless child so much pain, and I had to remind myself that parents cause their children pain in many different cultures, including mine (with male circumcision, ear piercing, etc.).

At the end of the cave tour, Mumtaz put me in a taxi heading for the airport, and I got on the plane feeling dizzy. I had just traveled most of the length of Egypt in less than six days.

Saturday, March 24, 2012

Long-needed Update

If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?

Albert Einstein

Here is a picture of a rainbow that I encountered over the Azraq Wetland Reserve. More on that later.

Wow. I haven’t posted in so long. Sorry about that. Things have been a bit crazy. After a pleasant series of visitors and an unpleasant series of bizarre illnesses, life is finally settling down into a routine and giving me some sense of normalcy.

Well, not quite yet. Later this week, I’m flying to Cairo for an impromptu tour around Egypt. My camera has run out of battery power and I lost my charger in a rental car, so hopefully I can borrow pictures from my friends. Update to follow!

I have finally finished my Arabic classes, and now I prepare for my research period. Two weeks ago, I carefully wandered my way around the University of Jordan campus for the first time, until I found my professor’s office. Over coffee and dates, we introduced each other in a cordial and professional manner.

Despite the formality, I immediately sensed the genuine kindness in his smile and words. I would occasionally address my research project, to which he patiently responded, “You have plenty of time to develop your project.”

Fighting my urge to jump in immediately, I know that if I’m going to do seismology, I have to really understand it. So, I’m starting off my research period by taking two classes, Seismology and Environmental Geophysics. Both in Arabic. Every morning, I take a creaky minibus to the University and sit in on my professor’s 90-minute lecture that tests my comprehension in Arabic, physics, and geology. I’m learning how to say words in Arabic that I never thought I would: nodes, electrical current, salt domes, perpendicular. My brain has never felt so numb after a class.

Meanwhile, I’m trying to define the boundaries of my project. I’m officially here, on paper, to determine if it’s possible to develop more accurate earthquake statistics for the region. From experience, I know I need to stay focused on the basic question. But now I’m realizing that I can use even more methods than I originally anticipated. I can study the underground structure of the fault that runs through Jordan using electrical sounding. I can use geographic information systems to plot the fault’s structure and location of earthquakes. Everything is so open-ended that I need to keep thinking and reading.

So that is my update for now! Upcoming entries include my relay half-marathon race from the Dead to the Red Sea, my Arabic-singing choir that I’ve joined, and how I’ve been learning how to recite the Quran.

I’ll write soon.

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

Hidden Passageways

“Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.”

This is my friend Mike, getting encouraged by a downtown salesman to show off how to properly wear a traditional Jordanian kufiah in the winter time.

Throughout Amman, I keep finding pathways. Shortcuts. Openings between buildings that can barely fit a human body. Stairs leading to somewhere, or sometimes leading to nowhere. No one else but me takes them.

Of course, I know I’m not the only person who knows these paths exist. I see hints and traces of previous travelers. I find empty potato chip bags and crushed soda cans, I glimpse a wiped-clean wall that still holds traces of vulgar or overly political graffiti, and I even notice that ancient doors with dusted-over locks line the shadowy passage ways.

What do those doors lead to? Why has no one opened them for so long? Why do these pathways feel so empty and unknown? The mystery of it entices me to continue walking along their silent trails.

I prefer taking them over the main roadways. Stepping down the quiet alleyways, hearing my own steps perfectly echoed along the cracked walls as if I’m wandering through a cathedral, I feel like I know the intimate details of Amman. I feel like I’m getting to know the raw, bare, loving, familial, prayerful soul that makes the city so characteristically special.

My love for walking along these pathways reminds of my love and yearning for making a unique difference in the world around me. Call it the American tendency for rugged individualism, but this urge to improve people’s lives using my interests and skills is the main motivation for why I’m here in this city. I keep thinking and wondering how I can possibly create a beneficial change with a combined love for geology and Arabic.

Well, here I am, studying Arabic and getting ready to embark on a nine-month long research initiative to better understand the seismic history of the region. Well, I suppose, if I want to make a truly unique, positive impression, I can’t expect the path to be entirely clear. I need to discover it, realize that it’s a possibility, and take the risk of going down it.